► Royal Navy ► Campaigns

W.L. Clowes on the New Zealand Wars of 1860 - 1863

Background information of the New Zealand Wars (sometimes referred to as the "Maori Wars") can be found of the following websites: HistoryOrb , New Zealand in History

, New Zealand in History and The New Zealand Wars

and The New Zealand Wars

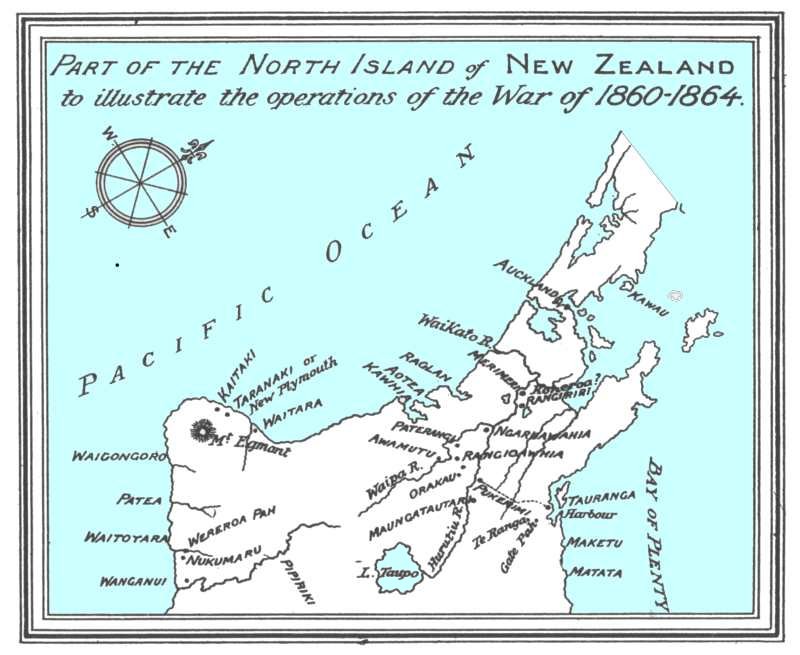

A renewal of the disputes over land-titles produced another native outbreak in the North Island of New Zealand early in 1860, the scene of hostilities being the neighbourhood of Taranaki, and the native leader being William King, the chief of the local tribe. A force, including two companies of the 65th Regiment, was sent to the spot, whither also the Niger, 13, screw, Captain Peter Cracroft, proceeded. A landing was effected at Waitara, on March 5th, no resistance being offered; and, on the following day, the ship was about to proceed to New Plymouth, when signals were made to her to the effect that the enemy, during the darkness, had built a stockade, which threatened to cut off the communication of the troops with their land base. King, however, eventually abandoned this stockade without fighting. On the 17th he was discovered to have erected another pah, which he resolutely defended, until a bombardment obliged him to quit it also. In the meantime, the Niger had gone to Auckland for supplies, leaving only a few of her people to assist the troops. On the 26th William King murdered three men and two boys, and boasted that he would drive the Europeans into the sea. On the 28th, therefore, by which day the Niger had returned, the naval detachment on shore accompanied the troops into the country to bring into town some settlers who lived in exposed and outlying places; and Cracroft, at the desire of Governor Gore Browne, landed further officers and men to hold the town during the absence of the expedition. He disembarked in person, with sixty seamen and Marines.

The rescuing force had not advanced more than four miles when it found itself warmly engaged with a strongly-posted body of the enemy. Word was sent back for reinforcements, and Cracroft went at once to the front with his men and a 24-pr. rocket-tube. King occupied a pah at Omata on the summit of a hill, and had severely handled the British force ere Cracroft's arrival; and of the small naval contingent, the leader, Lieutenant William Hans Blake, had been dangerously wounded, and a Marine killed. Cracroft determined to storm the pah, and, addressing his men, pointed to the rebel flag, and promised L.10 to the man who should haul it down. He then moved to within 800 yards, and opened fire from his rocket-tube, which, however, made no impression. It was then nearly dark, and Colonel Murray, who led the military force, announced his intention of retreating to the town, whither he had been ordered to return by sunset, and advised Cracroft to do the same. "I purpose to take that pah first," said the Captain. The visible withdrawal of the troops from the front of the position probably had the effect of rendering the enemy more careless than he might otherwise have been to what was going on on his flank. The result was that Cracroft managed to get close up to an outlying body of natives before his presence was detected. Within 60 yards of the enemy he gave the word to double. With a volley and a cheer the men were instantly in the midst of the rebels, who, after a brave resistance, took refuge in the pah behind them, or escaped. The seamen and Marines rushed onwards, met tomahawk with bayonet, and soon annihilated all resistance. Cracroft, who had not force enough to hold the position with, returned leisurely with his wounded, who were not numerous, and was not molested. On the following day, the enemy retired to the southward, having lost very heavily. It should be added that William Odgers, seaman, who was the first man inside the pah, and who pulled down the enemy's flag, was awarded the Victoria Cross.

Hostilities continued. On June 23rd a reconnoitring party of troops was fired at near Waitara; and, in consequence, an attack, with insufficient force (three hundred and forty-seven in all; the natives were thrice as numerous), was made on a strong rebel pah in the immediate neighbourhood on June 26th, in the early morning. Part of the 40th Regiment, some Royal Engineers, and a small Naval Brigade under Commodore Frederick Beauchamp Paget Seymour, of the Pelorus, 21, screw, were engaged. After a hot fight, lasting for more than four hours, the British were obliged by overwhelming forces to retreat, after having lost 29 killed and 33 wounded, among the latter being Seymour, eight seamen, and one Marine. Besides Seymour, the naval officers engaged were Lieutenant Albert Henry William Battiscombe, Midshipmen Ernest Bannister Wadlow, and ----- Garnett, and Lieutenant John William Henry Chafyn Grove Morris, R.M.A.

The war was somewhat more actively prosecuted after the arrival on the scene of Major-General T.S. Pratt, who won an initial success, and then, on December 29th, with troops, guns, and 138 officers and men from the ships (chiefly from the Cordelia and Niger; and from colonial steamer Victoria.), under Commodore Seymour, entrenched himself at Kairau, opposite the strong position of Matari-koriko, which, during the two following days, he obliged the enemy to evacuate. He fought the action entirely with cannon, rifle, and spade, and, not unduly exposing his men, had but 3 killed and 21 wounded. After this success, Pratt adopted the practice of reducing the successive positions of his opponents by means of regular approaches. These tactics broke up the rebel combinations. A chief named William Thompson, whose tribe, the Waikato, had joined the Taranaki natives, finally proposed a suspension of hostilities, and on May 21st, 1861, a truce was arranged. Governor Gore Browne had mismanaged matters; and he would, almost immediately, have provoked a new outbreak had not the home Government, realising that the position of the colony was becoming serious, recalled him by means of a dispatch which, while otherwise complimentary, informed him that he was superseded by Sir George Grey, who, as has been seen, had already been appointed governor in 1845, and who had since governed the Cape.

Grey seems to have used his best endeavours to pacify the natives. He even offered to submit the still unsettled land questions to arbitration by two Europeans and four Maoris, three to be appointed by him and three by the natives. This was refused. Grey then determined to abandon the disputed territory at Waitara, but to insist upon the restitution of the district of Tataraimaka, which had been seized by the rebels and held by them since 1861, in spite of the fact that there was no doubt whatsoever of the validity of the purchase of it in 1848 or 1849. Unfortunately, as it turned out, he sent a force to occupy Tataraimaka, without simultaneously proclaiming his intention of giving up Waitara. The resident natives made no opposition, but sent to William Thompson, of Waikato, for orders. He and the other leaders of the King party decided for war; and the Maoris at once began operations by falling upon a small escort party on May 4th, 1863, and murdering two officers and eight rank and file of Imperial troops. Grey then committed a worse mistake. He announced hurriedly that Waitara was to be abandoned, thereby encouraging his enemies, and sapping the attachment of his friends among the natives by unwittingly suggesting that he was influenced by fear and the consciousness of weakness. A few weeks earlier, Mr. John Eldon Gorst,1 civil commissioner in the Waikato country, who had established a newspaper there to combat the teachings of Kingism, had had his press and material violently seized by the partisans of the King paper, Hokioi; and the timber ready for the erection of a court-house and barracks in lower Waikato had been forcibly taken and thrown into the river, while Mr. Gorst had been expelled soon afterwards.

Aware, after what they had done, that they were committed to a serious struggle, the natives determined to invade Auckland; and Grey, getting early intelligence of their intention, decided to forestall matters by advancing into the Maori country. The senior military officer, Lieut.-General D.A. Cameron, C.B., who was at New Plymouth, endeavouring to punish the perpetrators of the massacre, was therefore recalled to Auckland, leaving behind him only enough troops to garrison New Plymouth; and the available British forces were soon afterwards concentrated along the Waikato river and the Maungatawhiri creek, the boundary between the settled districts and the unsold Maori lands. The boundary was crossed on July 12th; on July 17th a small British detachment was defeated between Queen's Redoubt and Drury; and on the same day a body of rebels was driven back and scattered near Koheroa; but then there ensued a long and almost inexplicable period of comparative inaction, so far as the army was concerned.

In the meantime, however, the Navy made itself useful. On June 4th, 1863, the Eclipse, 4, screw, Commander Richard Charles Mayne, co-operated in an attack which was made by the garrison of New Plymouth on a rebel position near the mouth of the Katikara; and on the night of August 1st, a detachment from the Harrier, 17, screw, Commander Francis William Sullivan, took part in a reconnaissance of Paparoa and Haurake. On August 3rd, Commander Sullivan, in the lightly-armoured colonial steamer Avon, also reconnoitred the Waikato river above Kohe-Hohe, and, for about half an hour, engaged a body of the enemy near Merimeri. On September 7th, the Harrier's boats, under Sullivan's direction, were employed to convey a force which was intended to support an unfortunate and costly raid made in the direction of Cameron Town.

While the army, under Lieut.-General Cameron, was getting ready for offensive operations, Commodore Sir William Saltonstall Wiseman, Bart., of the Curacoa, 23, screw, who, in April, had been appointed senior officer on the Australian station, concentrated as large a proportion as possible of his available strength in New Zealand waters, and himself left Sydney, with troops on board, and one or two vessels in company, on September 22nd, arriving at Auckland on October 2nd. The Curacoa herself at once landed 232 officers and men, who were sent up country to the support of the troops; and she remained as guardship at Auckland under Lieutenant Duke Doughton Yonge, with but three other officers and 90 men in her. She was kept ready for action in case of a sudden descent of the Maoris on the town. The other ships which then, or soon afterwards, co-operated with the senior officer in New Zealand waters were the

Miranda, 15, screw, Captain Robert Jenkins

Esk, 21, screw, Captain John Fane Charles Hamilton

Harrier, 17, screw, Commander Francis William Sullivan (Capt. Nov. 9th, 1863. He was succeeded by Com. Edward Hay)

Eclipse, 4, screw, Commander Richard Charles Mayne (after Mayne's disablement, Lieut. Henry Joshua Coddington acted until the arrival of Com. Edmund Robert Fremantle)

Falcon, 17, screw, Commander George Henry Parkin

Besides the Pioneer, Avon, Sandfly, Corio, and other colonial vessels.

Late in October, General Cameron and Commodore Wiseman, in the colonial steamer Pioneer, made two reconnaissances up the Walkathon, pushing, on the 31st, as far as Rangariri. On that occasion they passed the strong Maori position at Merimeri, and, having discovered a good landing-place about six miles above it, it was arranged with the Commodore to embark a force from Queen's Redoubt. This force, in the colonial steamers Pioneer and Avon, with four lightly-plated gunboats in tow, got under way at 2.30 on the morning of November 1st, and reached the landing-place at about 6 A.M. (these gunboats, named Flirt, Midge, Chum and Ant, were originally cargo boats, and were thinly armed by Capt. Jenkins at Auckland, and then transported by him overland, via Manakau, to the Waikato). The troops disembarked unopposed, and began to construct a breastwork, pending the arrival of further forces. In, the afternoon, however, the natives at Merimeri, seeing that their position had been turned, abandoned their works, and made off in canoes up the Maramarua and Whangamarino creeks. Cameron at once proceeded to Merimeri, and occupied it with a force which included 250 seamen under Commander Mayne. The place was afterwards fortified.

Between November 16th and November 25th, an expedition, under Captain Jenkins and Colonel G.J. Carey, was engaged to the northward, and up the Firth of Thames, to the eastward of the country occupied by the enemy. It was made in the Miranda, Esk, Sandfly, and Corio. Although it took possession of some positions, and so accomplished part of its purpose, it did not come into actual collision with the enemy, and was therefore unable to deal any serious blow. The Miranda remained for a time in the Firth of Thames. During the absence of the expedition an important success was won on the Waikato.

After the abandonment of Merimeri, a strong force of rebels entrenched themselves at Rangariri, a village about twelve miles higher up the river. There, on November 20th, General Cameron, with troops, the four plated gunboats, and a Naval Brigade from the Curacoa, Miranda, Harrier, and Eclipse, under Commodore Wiseman, numbering about 400 men, attacked them. He had in all about 1200 men, while the Maoris were but about 400; but the latter had the advantage of a strong position, though it was one from which there was no easy way of retreat, and one, too, which required a much larger force to hold it properly. The two divisions did not arrive simultaneously before the works. One, coming by land, threatened the front, while the other, brought in the steamers, was to have threatened the rear; but part of the latter was delayed by the strength of the current. For an hour and a half the position was bombarded, and then, at 4.30 P.M., an assault was ordered. The Maoris soon concentrated themselves in a very formidable redoubt in the centre of their lines, and bloodily repulsed four separate attempts to carry it - one by the 65th Regiment, one by a party of Royal Artillerymen, and two by 90 men of the Naval Brigade, gallantly led by Commander Mayne and Commander Henry Bourchier Phillimore. It was then nearly dark. An attempt on the part of some of the brave defenders to get away across Lake Waikarei, and a swamp on their right flank, was partially prevented by the 40th Regiment, and a detachment of the Marines, who, having by that time arrived by water, had moved round to the rear; but it was supposed that two of the most important leaders, King Matutaere, and William Thompson, escaped ere the way was blocked. The rest were trapped, and, although they kept up a desultory fire during the night, they surrendered unconditionally on the morning of November 21st. Those who thus gave themselves up numbered 183 men and 2 women. The others had fallen or had escaped. It had been a magnificent defence; and the success was a very costly one; for, on the British side, 36 were killed and 98 wounded, many mortally. (The British tactics at Rangiriri were adversely criticised at the time. The enemy was driven, without much trouble or loss, into the central redoubt, where he might have been either approached by sapping, or starved into surrender, if he had not previously succumbed to bombardment. Instead, he was stormed, at great expenditure of life. Fox thinks that he might have been reduced, with little or no loss, in a few hours, as he could not escape.) The naval casualties were 5 killed, including Midshipman Thomas A. Watkins (Curacoa), and 10 wounded, including Commander Mayne (Eclipse; Capt., Feb. 12th, 1864), and Lieutenants Edward Downes Panter Downes (Miranda; Com., Feb. 12th, 1864), Henry M'Clintock Alexander (Curacoa; Com., Feb. 12th, 1864), and Charles Frederick Hotham (Curacoa). After the surrender, William Thompson, with a small party, approached the place with a white flag, but, having parleyed, withdrew again, not being able to make up his mind to submit.

In addition to the naval officers already named, the following were mentioned in the dispatches: Captain Francis William Sullivan; Lieutenants Charles Hill, and William Fletcher Boughey; Acting-Lieutenant Robert Frederick Hammick (Lieut., Feb. 12th, 1864), commanding the small gunboats; Sub-Lieutenant Frederic John Easther, commanding the Avon; Midshipmen Sydney Augustus Rowan Hamilton, Frank Elrington Hudson, and Cecil George Foljarnbe; Assistant Surgeons Adam Brunton Messer (Surg., Feb. 12th, 1864), M.D., and Duncan Hilston, M.D.; and ordinary seaman William Fox (Curacoa).

The prisoners were temporarily confined on board the Curacoa, at Auckland.

For some days after the action, the flotilla was laboriously employed in bringing up supplies to Merimeri, Rangiriri, and Taupiri, to which last the General advanced on December 3rd. On the same day, Commodore Wiseman and Captain Sullivan, having lightened the Pioneer by removing the armoured turrets from her, pushed on in her to Kupa Kupa Island, about four miles ahead of the troops. Immense natural difficulties were encountered, but no enemy was seen.

There is no doubt that the Maoris were, for the moment, greatly disheartened; for, on December 8th, without further resistance, General Cameron was allowed to occupy Ngaruawahia, at the junction of the Hurutiu and Waipa rivers, which together form the Waikato. Ngaruawahia was an important political centre, as it had been the headquarters of Kingism, the burial place of King Potatau, and the capital of his successor Matutaere. If Sir George Grey had seen his way to go thither to negotiate, as, at one time, he intended, terms might then have been arranged. Instead, he wrote to the natives that he would receive a deputation from them at Auckland. It is, however, not certain that William Thompson, the leading spirit, then really desired peace; for no reply to the Governor's letter was ever received. Cameron remained for some time at Ngaruawahia to collect supplies, but, at the end of January, moved up the Waipa, and arrived before Pikopiko and Paterangi, two posts which were very strongly fortified. While this movement was in progress, Lieutenant William Edward Mitchell, of the Esk, who was in command of the Avon, was fatally wounded by a chance shot from Maoris in ambush on the river bank. He was only two-and-twenty years of age. Acting-Lieutenant Frederic John Easther, of the Harrier, succeeded him in command of the Avon.

Before the Miranda quitted the Firth of Thames, all the posts between that estuary and Queen's Redoubt, on the Waikato, were taken possession of, and held by detachments of the 12th and 70th Regiments, the Waikato militia, or the Auckland Naval Volunteers, which had been brought round with the expedition commanded by Captain Jenkins. On January 20th, 1864, with troops under Colonel Carey, of the 18th Royal Irish, Jenkins weighed, and proceeded down the coast to Tauranga, leaving the Esk in the Thames. The Miranda, which was accompanied by the Corio, encountered no resistance on the shores of the Bay of Plenty; and, when the troops had established themselves at Te Papa, the natives at first supplied them with provisions, though afterwards they became less willing to assist them.

At that time, the Curacoa was at Auckland, while most of her people, under the Commodore, were serving at the front; the Harrier was in the Thames or at Manakau, also with most of her people at the front; and the Eclipse was in the Waikato, with a detachment, under Lieutenant William Fletcher Boughey, co-operating with the troops. Sir Duncan Cameron lay for some weeks in the neighbourhood of the native strongholds of Pikopiko and Paterangi; but on the night of February 20th, he turned those positions by making a sudden flank march to Awamutu. The formidable works on the Waikato were instantly evacuated by the Maoris, who concentrated at Rangioawhia, where, on the 22nd, they were defeated, with considerable loss in killed and prisoners. The majority of the rebels in what are now Waikato, Raglan, and Waipa counties then retired to Maungatautari, a stronghold on the Hurutiu. During these operations the Navy appears to have suffered no loss; and in the few succeeding movements which terminated what has been called the Waikato campaign, the Navy had practically no share.

In April, Sir Duncan Cameron had his headquarters at Pukerimu, on the Hurutiu, a place only about forty miles as the crow would fly, from Tauranga, on the east coast. Most of the Tauranga people had been engaged in the actions in Waikato; and on April 1st, the Miranda, lying in the Bay, had been obliged to disperse a number of them who had come down to the coast in a threatening manner. Lieut.-Colonel Greer, 68th Regiment, had by that time succeeded Colonel Carey in command at Te Papa; and, believing his position to be precarious, he asked Sir Duncan Cameron for reinforcements. Cameron not only sent them, but also went himself to Tauranga, and procured the assistance of some of the squadron in conveying thither a part of the troops. The landing of these was completed on April 26th. The force then ashore numbered 1695 of all ranks, and included 429 officers and men from the Curacoa, Miranda, Esk, Eclipse, and Falcon. In the Bay were the Miranda, Esk, and Falcon, together with the colonial steamers Sandfly, Alexander, and Tauranga. The troops consisted mainly of the 43rd, 68th, and 70th Regiments, some Royal Engineers, and some Royal Artillery; and the guns landed were: one 110-pr. Armstrong, two 40-pr. Armstrongs, two 6-pr. Armstrongs, two 24-pr. field howitzers, two 8-in. mortars, and six coehorn mortars, A body of Maoris, said not to have exceeded 300 in number, and alleged by themselves not to have exceeded 150, had constructed a formidable work about three miles from Te Papa, on a neck of land which on each side fell off into a swamp. It is known in history as the Gate Pah. On the highest point of the neck was an oblong palisaded redoubt; and from the redoubt to the swamps were lines of rifle-pits. The rear of the position was accessible, though with difficulty; and across it Colonel Greer, with the 68th Regiment, succeeded in posting himself on the night of April 28th (on that day the Falcon had shelled the enemy out of a position at Maketu, and driven them along the beach to Otamarakau), while a feigned attack was being made on the enemy's front; and he stationed himself in such a manner as to cut off the supply of water to the work, and also, theoretically, to be able to intercept the retreat of the garrison. It is clear that the rebels, deprived of their water, and having no guns, might have been easily reduced without any resort on the part of Cameron to the costly and disastrous tactics which he chose to pursue.

The guns were planted in four positions at distances varying from 800 to 100 yards from the pah; and soon after 6.30 A.M. on April 29th, after the Maoris had fired a volley at the British skirmishers, the guns opened simultaneously. Sir Duncan Cameron reported that the practice was excellent, but other eye-witnesses have declared that it was extremely wild. The rebels lay low in their schanzes, and made but little reply. At about noon, a 6-pr. gun was taken across the swamp on the enemy's left, and hauled on to the high ground, whence it enfiladed the rifle-pits on that side and presently caused their abandonment. The latter part of the bombardment having been directed chiefly against the left angle of the main work, the fence and palisades in that neighbourhood were destroyed, and a breach was effected by 4 P.M., when Cameron ordered an assault. For that purpose, 150 seamen and Marines, under Commander Edward Hay of the Harrier, and an equal number of the 43rd Regiment, under Lieut.-Colonel Booth, had been told off. In addition, 170 men of the 70th Regiment had been directed to extend, keep down the enemy's fire until the last possible moment, and then follow the assaulting column into the breach; while the rest of the seamen and Marines, and of the 43rd, were to bring up the rear as a reserve.

The assaulting column, favoured by the folds of the ground, gained the breach with but little loss, and entered the works, the 68th, from the rear of the position, closing up at the same moment and driving back the Maoris, who were already attempting to bolt. Inside the pah the rebels fought with desperation, both Hay and Booth being mortally wounded soon after they had got through the breach. But the place would have been carried had not a panic, which Cameron professed himself unable to explain, seized the assaulting column, or, rather, as would appear, the part of it belonging to the 43rd. The men turned round, communicated the contagion to their fellows, and rushed out pell-mell, shrieking, "There's thousands of them"; and in an instant they were flying madly back. Captain John Fane Charles Hamilton, of the Esk, with the reserve of the Naval Brigade, pushed up, but was shot dead on the top of the parapet. Nothing could be done to stop the disgraceful retreat; and the rebels, boldly showing themselves and firing into the backs of the fugitives, did terrible execution.

The force was at length rallied; but Cameron cared not to renew the assault. Instead, he ordered a line of entrenchments to be thrown up within a hundred yards of the pah, intending to conduct further operations on the following morning.

The night of the 29th was extremely dark. For a time the rebels, as was their custom in such circumstances, howled and shouted. Suddenly the noises ceased, and the sound of firing was heard from the rear. The Maoris, with very little loss, had escaped through the lines of the 68th; and a British officer who crept into the pah at about midnight found it completely evacuated, save by a few British wounded, who had not been maltreated. Cameron, in his dispatch, says that the loss of the natives must have been very heavy, yet admits that only about 20 Maori killed and 6 wounded were found about the position. Natives afterwards estimated their total loss at no more than between thirty and forty.

"Allowing," says the correspondent of the Times, "that the best way of taking a Maori pah is to storm it in front, everything was done that skill and diligence could do to this end." The premise can hardly be admitted, seeing that Cameron had means of knowing that the pah was waterless, and therefore could not be held by the enemy for many hours; nor, even admitting the premise, can the conclusion be granted. One of the rules of war is that, when a force of given strength has to be employed, a homogeneous force is better than a mixed one, unless it be necessary to utilise more than one arm, as, for example, cavalry and infantry. Another rule is to employ for any given service the force best suited by tradition and training for the work in hand. Cameron had with him nearly 300 officers and men of the 43rd, and more than double that number of the 68th; yet, instead of taking what he appears to have deemed the necessary detachment of men for the assault from one of those corps, he took 150 from the 43rd, and added to them, not 150 from the 68th, but 150 from the Naval Brigade, a force which, looking to all the circumstances, ought, I venture to think, to have formed the reserve, and to have been given no other post. No doubt, the Navy craved to be allowed to share the dangers of the storm; but to say that is far from saying that the General was wise in permitting it to do so. It should be added here that at Te Kanga, on June 21st following, the 43rd amply redeemed its laurels.

The lamentable affair of the Gate Pah cost the British no fewer than 27 killed and 66 wounded. Of this tale, the casualties of the Navy were 3 officers and 8 men killed or mortally injured, and 3 officers and 19 men wounded. The officers who lost their lives were Captain John Fane Charles Hamilton (Esk; aged 42 ; a Capt. of 1858), Commander Edward Hay (Harrier; aged 28; a Commander of 1858. A memorial to those of the Harrier's people who fell in New Zealand was erected in 1865 in Kingston Church, Portsmouth), and Lieutenant Charles Hill (Curacoa; a survivor of the wreck of the Orpheus); and the officers wounded were George Graham Duff (Esk), Lieutenant Robert Frederick Hammick (Miranda), and Sub-Lieutenant Philip Keginald Hastings Parker (Falcon).

The Naval Brigade behaved admirably, and retired only when nearly all its leading officers had been shot down. The Commodore and Captain Jenkins had most marvellous escapes. After Commander Hay had been mortally hit, a seaman named Samuel Mitchell went to his assistance, and, although ordered by his officer to leave him and consult his own safety, carried Hay out of the pah. The act of devotion gained the brave fellow the Victoria Cross.

In recognition of the gallantry displayed by the Navy in New Zealand, and especially in the affair of the Gate Pah, the Admiralty made the following promotions:-

To be Captain: Com. Henry Bourchier Phillimore (July 14th, 1864).

To be Commanders: Lieut. George Graham Duff (Ap. 29th, 1864); Lieut. Charles Frederick Hotham (upon completing sea-time, Ap. 19th, 1865); Lieut. John Thomlinson Swann (July 14th, 1864).

To be Lieutenants: Sub-Lieut. Philip Reginald Hastings Parker (Ap. 29th, 1864) Actg.-Lieut. Archer John William Musgrave (on passing required examination, to date Ap. 29th, 1864); Sub-Lieut. Paul Storr (July 14th, 1864); Sub-Lieut. John Hope (July 14th, 1864).

In addition, the names of Lieuts. Robert Sidney Hunt, and Robert Frederick Hammick, and Lieut. (R.M.A.) Robert Ballard Gardner, were ordered to be favourably noted.

In the latter part of this unfortunate war, which dragged on for a considerable period, and which owed its prolongation not only to the bravery of the enemy, but also to the supineness and divided counsels of the British, the Navy had comparatively little share; nor was it called upon to do anything of importance in connection with the repression of the brief New Zealand rebellion of 1869. Among the vessels which were more particularly concerned, especially in the earlier part of the period, were the Eclipse, 4, Commander Edmund Robert Fremantle; Brisk, 16, Captain Charles Webley Hope; and Esk, 21, Captain John Proctor Luce.

Top↑

|